The Problem with Generic AI Translation in Legal Contexts

The discussion around AI in translation tends to gravitate toward two extremes: either enthusiastic predictions of fully automated multilingual communication, or categorical rejection of any machine involvement in specialised domains. Both positions, while understandable, overlook the more nuanced reality of how AI can be meaningfully integrated into professional workflows – particularly in legal translation, where precision is not merely desirable but constitutive of the output’s value.

The translation of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) presents a case in point. These documents require not only accurate rendering of legal concepts, but also consistency with decades of established terminology, adherence to specific citation formats, and awareness of the structural conventions that distinguish, for instance, references to the European Convention on Human Rights (art. X ust. Y Konwencji) from references to the Rules of Court (Reguła X § Y Regulaminu). A single terminological error – translating “margin of appreciation” as “margines uznania” rather than the established “margines oceny” – shifts the legal meaning from an objective standard of assessment to a subjective margin of discretion.

Conventional CAT tools and general-purpose AI translation models are structurally unable to address these requirements. They lack the capacity to cross-reference case-law databases, to distinguish between terminological conventions across legal instruments, or to apply the specific editorial rules governing ECtHR translation practice. This gap between what exists and what the domain demands motivated ECTHR Translator – a multi-agent AI system designed specifically for the professional translation of ECtHR judgments from English into Polish.

The concept and the domain knowledge embedded in this system did not emerge from theoretical modelling. They are the product of many years of hands-on experience of the IURIDICO team in translating case law of the European Court of Human Rights, the Court of Justice of the European Union, and more broadly, documentation from the field of human rights protection. It is this accumulated professional practice – the nuanced terminological choices made across hundreds of judgments, the editorial conventions internalised through daily work with these texts, the understanding of how a single word can alter legal meaning – that informed the detailed and highly specific agent instructions at the core of the system. In other words, the AI was trained to translate as a seasoned legal translator would: not by guessing from context, but by following a structured methodology grounded in authoritative sources and validated by human expertise.

Architecture: A Pipeline That Mirrors Professional Practice

The system’s architecture was not designed from abstract principles of software engineering, but rather modelled on the actual workflow of a legal translator handling ECtHR judgments. In professional practice, the translation process follows a well-defined sequence: document analysis, terminological research across authoritative sources, translation with mandatory terminology constraints, expert review, and quality assurance. Each stage requires different competencies and different tools.

ECTHR Translator codifies this workflow into a pipeline of seven specialised agents, coordinated by an Orchestrator.

The pipeline processes documents in batches of 10 segments. For each batch, the Term Extractor identifies legal terms, the Case Law Researcher verifies them against authoritative databases, and the Translator produces a draft using the resulting mandatory terminology. After human validation of every terminological decision, the Change Implementer retranslates the affected segments, and the QA Reviewer runs 11 automated checks before the final DOCX is assembled, preserving the original formatting.

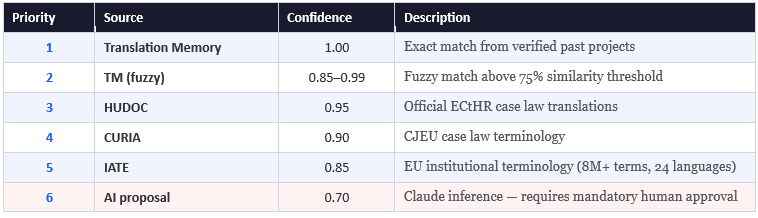

The Source Hierarchy: Authoritative Knowledge Before AI Inference

Perhaps the most consequential architectural decision concerns the order in which the system consults its sources. Unlike most AI-powered translation tools, which generate a translation first and optionally verify it against a glossary, ECTHR Translator inverts this logic entirely. The system starts with authoritative legal sources and uses AI only when all other sources have been exhausted. At the foundation of this hierarchy sits the Translation Memory: a curated repository of terminological decisions verified and approved by human translators across previous projects. This is not a static database but a living resource that grows with each assignment, preserving the translation team’s institutional knowledge in a structured, reusable form.

The system applies early stopping: once a match is found at a given priority level, the lower-priority sources are not consulted. If the Translation Memory contains a verified equivalent from a previous project, the system uses it directly. If not, it searches HUDOC for official ECtHR translations, then CURIA for CJEU terminology, then IATE for broader EU institutional usage. Only when all these databases return no result does the AI propose its own translation — and even that proposal is flagged with a lower confidence score and routed to the human expert for mandatory approval.

This design reflects a fundamental principle: in specialised legal translation, the model’s linguistic competence is necessary but insufficient. What matters is terminological accuracy grounded in institutional practice, and that accuracy comes from authoritative sources, not from probabilistic inference.

86 Rules: Encoding Professional Expertise

The Translator agent operates on a prompt comprising 86 rules specific to ECtHR translation practice. These are not generic quality guidelines. They are codified workshop instructions — the same principles that the IURIDICO team applies in daily professional practice and that form the basis of internal training for new translators joining ECtHR projects. Each rule addresses a concrete terminological, structural, or typographic convention that has proven consequential across hundreds of translated judgments:

Terminological precision. “Applicant” renders as “skarżący” (not “osoba skarżąca”). “Registrar” is “Kanclerz” (not “Sekretarz”). “Fair trial” is “rzetelny proces” (not “sprawiedliwy proces”). “Alleged violation” is “zarzucane naruszenie” (not “domniemane”). Each of these distinctions carries specific legal weight and is established by consistent institutional usage.

Structural conventions. The ECHR uses “art. X ust. Y,” while the Rules of Court use “Reguła X § Y.” The current judgment references paragraphs in words (“paragraf 34 powyżej”), while cited judgments use the § symbol (“§ 45 wyroku X p. Y”). Confusing these systems is one of the most reliable indicators of a non-specialist translation.

Citation format. ECtHR cases follow the pattern: “w sprawie Reczkowicz przeciwko Polsce (skarga nr 43447/19, §§ 59–70, 22 lipca 2021 r.)” – with an en dash, not a hyphen, between paragraph numbers. CJEU cases omit “nr” before case numbers and use “połączone sprawy” for joined cases.

Polish legal register. Postpositive word order, impersonal constructions, archaic forms characteristic of judicial language (“zważywszy,” “albowiem”), Polish quotation marks („…”), and non-breaking spaces after single-letter prepositions. The model operates at a temperature of 0.3, prioritising consistency over creativity – the appropriate setting for legal translation.

Human-in-the-Loop as a Design Principle

The system’s validation interface routes every extracted term to the human translator, who sees the English source, the proposed Polish equivalent, the confidence score, and the source database. Three actions are available: approve, edit, or reject. This is not a cursory review step; it is the central mechanism through which professional expertise enters the system. The translator evaluates each proposal against the specific context of the judgment, the conventions of the relevant legal instrument, and the established terminological practice of the field. Approved terms automatically feed back into the Translation Memory, creating a virtuous feedback loop: each validated decision enriches the TM, which in turn improves the accuracy and consistency of future projects. Over time, the system reflects the team’s collective terminological judgement.

This is not a concession to imperfect technology. It is a deliberate design choice rooted in the conviction that in legal translation, the translator’s professional judgement is not an optional layer of quality assurance — it is the product itself. The system accelerates the research and drafting phases that consume the most time. The terminological decisions, which constitute the actual value of professional legal translation, remain with the expert.

As argued in earlier publications, AI in this context should be understood as a tool that enhances professional capability rather than a replacement for domain expertise. The distinction is not merely semantic. Clients of legal translation – courts, law firms, and international organisations – require trust in the output. That trust rests on knowing that a qualified specialist made the final call on every term, informed by authoritative sources rather than unchecked machine inference.

Practical Impact

A 10-page ECtHR judgment that previously required a full working day of research and translation now reaches the human validation stage in approximately 15 minutes. The shift is primarily in how the translator’s time is allocated: from searching databases and cross-referencing case law – work that the system now handles automatically – to reviewing proposals and making informed decisions. After human validation, the accuracy of terminology reaches 99%. The QA module detects formatting inconsistencies (incorrect quotation marks, missing non-breaking spaces, hyphens where en dashes are required) that even experienced translators miss under time pressure.

Broader Implications for Language Technology in Legal Practice

Three observations from this project may be relevant to the broader discussion about AI in specialised translation and legal practice.

First, domain knowledge is the actual differentiator. The technical infrastructure for connecting a large language model to a translation interface is widely accessible. What is not easily replicable is the body of domain-specific rules, terminological hierarchies, and institutional conventions that distinguish a competent professional translation from a superficially fluent but substantively flawed one. In the case of ECTHR Translator, this knowledge – the 86 translation rules, the source hierarchy, the structural conventions – came from the collective experience of a team that has been translating ECtHR and CJEU case law for years, building Translation Memories, refining terminological choices, and developing internal quality standards. No amount of training data can substitute for this kind of situated, practice-derived expertise.

Second, the multi-agent pattern maps naturally onto expert workflows. The decision to use a multi-agent architecture was not driven by technological fashion, but by the structure of the work itself. Legal translation is not a single task; it is a sequence of distinct operations (structural analysis, term extraction, source research, translation, quality assurance), each requiring a different context and different tools. Modelling this as a pipeline of specialised agents mirrors how a professional translation team operates – except at a pace that no human team can sustain.

Third, the question of who controls the final output remains paramount. As AI systems become more capable, the temptation to reduce human involvement grows. In high-stakes domains such as legal translation for courts and international tribunals, this temptation should be resisted. The value proposition of ECTHR Translator is not that it produces “AI translations.” It is that it produces translations by a human expert, significantly accelerated by AI-powered research and intelligent drafting. The distinction is both ethically and practically consequential.

Next Steps

The architecture of ECTHR Translator is designed to be extensible. Additional language pairs (DE-PL, FR-PL), integration with SDL Trados via SDLXLIFF, collaborative editing for translation teams, and fine-tuning on ECtHR corpora are on the development roadmap. Further work is planned to expand the Translation Memory infrastructure and refine the QA module to address an even broader range of domain-specific quality checks.

Feedback, questions, and inquiries about collaboration are welcome – whether from legal translators, language technology developers, or professionals working at the intersection of law and AI.

Stack: Python 3.11 • FastAPI • React 18 • Anthropic Claude API • SQLAlchemy • WebSocket